49-year-old Hajj Ramadhan Omar cannot help but reminisce about his past fishing days.

Omar who learned how to fish using his wooden canoe from his late grandfather says he could trap up-to 50 kilograms of prawns before 2013, a sharp contrast the three kilograms he caught on the day he spoke to Baraka FM.

Omar who is a member of the Tudor-Shimanzi beach management unit in Mombasa county says his woes started after private developers controversially acquired title deeds for the land at the Kibarani area and went ahead to reclaim more land from the ocean.

“The reclamation process started in 2013 and they did not reclaim just anywhere, they reclaimed areas where prawns and lobsters would breed” Omar says.

Omar says the dwindled catches have forced some of his peers to ditch fishing and venture into other activities but for him, he has chosen to stay as he argues its the only skill he inherited from his late father.

” Where do I go once I stop fishing, I did not inherit the land where I can farm, fishing skills and gear is what I inherited” Omar poses.

In neighboring Kisauni sub-county, 59-year-old Kazungu Shughuli stares at a structure that once sheltered him and his fellow fishermen from the scorching sun after their fishing expeditions and whenever they had their BMU(Beach Management Unit) meetings.

The temporary structure has since caved in forcing Kazungu and his fellow fishermen from the Kidongo beach management to limit their catches to preorders in order to avoid incuring losses occasioned when their unsold catches rot due to lack of a cold storage facility.

According to Kazungu, their problems began when three private owners started claiming ownership of their Mwakusea triangle landing site and the Kenya Prisons Service built a wall blocking them access to their Old Ferry landing site pushing them to operate from the Kidongo site.

Despite their 10-kilometer landing site being one of the few that are gazetted by the National lands commission, they had not yet been issued with a title deed to claim ownership of the land.

“A donor had offered to help us built a permanent office with a cold storage facility to help us preserve our catches during the peak season. However, when we failed to produce a title deed, the donor told us it was pointless to build a permanent structure on land we did not possess the ownership documents” Kazungu says.

Omar and Kazungu are among the 3000 fishermen who have fallen victim to unending land ownership issues in Mombasa which activists argue have hindered the productivity of the marine fishing industry in the country.

A 2015 report dubbed Nowhere to land by local human rights group Haki Yetu stated that fishermen in the county could only access less than 40% of their landing sites after the rest were grabbed by government agencies and private developers who include luxurious beach hotels.

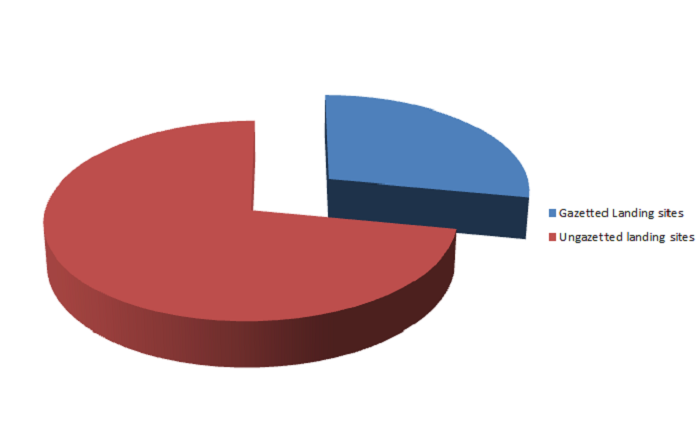

The report argued that the grabbers had exploited the fact that before 2018 only 14 landing sites out of the 50 in the county had been gazetted and none had been issued with a title deed.

“This had, therefore, resulted in grabbing of several fish landing sites by industries, government parastatals, hoteliers, and greedy opportunists who had encroached upon the landing sites and evicted the poor fisherfolk.” The report stated.

The fishermen breathed a sigh of relief in 2018 after President Uhuru Kenyatta directed government agencies to repossess and issue title deeds for grabbed landing sites by April 2019.

The directive came just a few weeks before the country hosted the first global blue economy conference.

Sh.300 million was released to facilitate the exercise in 2019 with government officials saying that Sh.500 million would be released to facilitate the exercise in 2020.

Whilst the fishermen were expecting that at least half of the fish landing sites would be recovered, only five of the 14 gazetted landing sites were mapped in the county.

This is according to Micheni Ntiba, the public secretary in charge of fisheries at the Ministry of agriculture who argues that it would have been an expensive exercise to map out all the landing sites.

“Dealing with all the landing sites in Kenya is expensive. We are at the final stage of recovering them. Since Uhuru’s directive we have been working day and night,” Ntiba said.

The five that were identified and mapped in Mombasa are: Tudor, Timbwani, Old Port, Mshomoroni and Kitanga Juu.

According to the report by Haki Yetu, only Timbwani, Tudor and Mishomoroni landing sites were in the hands of grabbers, Old town and Kitanga Juu were still accessible to fishermen though they did not possess the title deeds.

However, this has been met by opposition from fishers and rights groups who argue that mapping only five out of the 14 gazetted landing sites for proper documentation is akin to encouraging grabbing of public land.

Last year, fishermen in Mombasa county wrote to the ministry of agriculture and the National lands commission demanding revocation of the mapping exercise.

“That you recall the decision to map out only five landing sites and direct the National Land Commission to fast track further repossession, surveying, and titling of all landing sites in Mombasa County. The process should be conducted transparently with the participation of fishermen and the Beach Management Units for the respective landing sites.” The fishermen wrote.

However, the exercise was not revoked; instead it proceeded to neighbor counties such as Lamu, Kwale, and Kilifi.

A report by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), states that the marine sector produces just 5% of the fish caught in Kenya.

According to Furaha Kyalo, a program officer with Haki Yetu, grabbing of fish landing sites negatively contributes to the productivity of the marine fishing industry.

“If a fisherman depends on a certain landing site for their livelihood, grabbing that landing site is taking away their livelihood meaning these people cannot sustain their families and the production of the fishing industry” Furaha says.

During the global blue economy conference, the government pledged to: “Accelerate development of marine and inland fishery industries by increasing aquaculture, fish processing, and storage capacities and related Blue Economy industries.”

But for fishermen like Omar and Kazungu, such pledges will only remain written on paper if the issue of grabbing of landing sites is not adequately addressed.

“If fishermen cannot access the beach conduct their fishing activity or landing sites which they can claim ownership to construct facilities such as cold storage rooms, it will be hard to improve their catches” Kazungu says.

This story is written with the support of REJOPRAH, Network of Journalists for Responsible Fisheries in Africa