Celestine Nyevu Ali cannot remember the last time she recorded a substantial catch of parrotfish.

Nyevu, 27, is the secretary of the Mayungu Beach Management Unit (BMU), the local association of 30 fishermen in Malindi, Kilifi County, and she is tasked with collecting and recording data on fish catches at her landing site.

“This is both in the peak and off-peak seasons. The catches are not substantial in a way that I can assure a client of an order of parrotfish,” Nyevu says.

According to available data collected by Nyevu, the fishermen in her BMU did not catch any parrotfish for the months of October to December last year.

This is in sharp contrast to the situation 11 years ago where data indicates that they caught 1,306 kilograms of parrotfish despite October, November, and December not being peak parrotfish months. (While peak season varies by species, in general, it extends between September and March).

Catches of other species have dwindled, too, forcing fishers to venture deeper into the ocean and double the time spent on fishing expeditions.

This, too, is seemingly not working.

According to the data collected by the Mayungu BMU, fishermen’s daily average catch between October and December has dropped by more than 72% from 2008.

The situation is worse in the nearby Watamu Beach Management Unit where a dozen fishermen have quit the trade after it turned into a loss-making entity.

“You find that the fishermen will feel discouraged after fueling a boat let’s say for 3,000 shillings and they end up catching nothing,” 51-year-old Athman Mwambire, the chairman of the Watamu BMU says.

CLIMATE CHANGE

Marine researchers in Kenya partly attribute the problem to ocean warming, which is driven by climate change.

According to a paper by Ocean climate, the warm ocean fuels coral bleaching, which is one of the leading causes of coral deaths.

“In the event of an extended bleaching episode, the coral dies of nutritional stress, leading to massive mortality in reef ecosystems worldwide, from the Pacific to the Indian Ocean, the Caribbean, and the Red Sea,” the paper says.

With coral reefs providing food and habitats to about one-third of the world’s marine species, the gradual death of these reef systems means a gradual reduction in fish species.

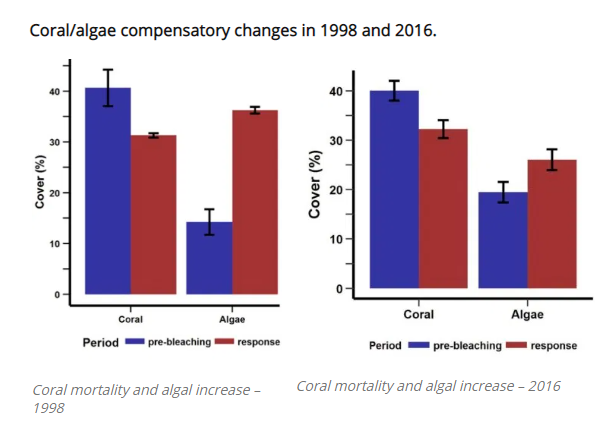

Research by Mombasa-based marine research organization CORDIO East Africa indicates that bleaching activity caused a significant growth in coral algae after the 1998 El-Nino Southern Oscillation event and the 2016 heatwaves.

“The impact of the 2016 bleaching was less than that of 1998, even though the two thermal stress events were broadly similar. In 1998 coral cover loss was 25%, compared to 20% in 2016. Algal cover increased 2.5 times in 1998, and again by 35% in 2016,” the organization says.

ENTER PARROTFISH

Too much algae can essentially suffocate reef ecosystems and kill off corals.

According to Peter Musembi, a marine researcher with CORDIO East Africa, after such an event, the presence of algae-eating herbivorous fish such as parrotfish helps coral reefs to recover.

However, as evidenced in the data provided by the BMU, parrotfish populations have been decreasing at a worrying pace trend.

“When herbivores are absent, faster-growing macroalgae can overgrow on reef substrate reducing space available for the settlement of juvenile corals. The macroalgae can also smother and kill surviving corals. And that’s what is happening in areas like Watamu where the coral cover has been steadily declining,” Musembi says.

READ ALSO:Rare giant sea mammal found dead in Pate Island

Researchers attribute the decline in parrotfish to overfishing and environmental degradation fuelled by problems such as marine pollution and climate change.

Though the majority of species of parrotfish commonly caught by small-scale fishermen in Kenya have been listed as ‘least concern’ by the International Union of Conservation of Nature(IUCN), the blue-barred parrotfish, which is commonly caught, has been listed as endangered.

With the worrying decline, fishermen have turned to rabbitfish, another class of herbivorous species that Musembi says performs the same function as parrotfish.

According to the data provided by the Mayungu BMU, rabbitfish were the most common fish trapped by fishermen for the months of October to December 2019.

Unlike parrotfish, Musembi says rabbitfish have a shorter maturity period, so they’re able to reproduce more quickly, though factors such as overfishing could cause a rapid decline in their populations.

COUNTRIES BAN PARROTFISH TRAPPING

As Mayungu fishermen struggle to come to terms with the effects of dwindled parrotfish populations, marine activists in the Caribbean have been advocating for fishers to stop the trapping of parrotfish.

In 2009, Belize became the first country to impose a complete ban on trapping parrotfish and surgeonfish, another common species of herbivorous fish with a 2018 report indicating that the ban has helped fuel a decline in the overgrowth of algae.

“In Belize, parrotfish biomass continues to increase (post-protection), with the first indication of a slight decline in fleshy macroalgae noted this year” the report indicated.

Similar restrictions are currently in place in Honduras, Guatemala, St.Vincent and Grenadines, and the Dominican Republic, and last year, México placed 10 species of parrotfish under special protection.

READ ALSO: Fish prices skyrocket in Taveta after Tanzanian supply is cutoff

A report by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) that blamed the degradation of corals in the Caribbean on dwindling populations of herbivores fish recommended having parrotfish listed under different annexes of the SPAW Protocol (Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife), a legally binding environment protection protocol currently in place among Caribbean countries.

“The most important recommendation based on the evidence of this report is the urgent and immediate need to ban fish traps and fishing of any kind for parrotfish and to severely restrict and regulate all other kinds of fishing throughout the wider Caribbean including spearfishing, gill nets, long lines, and all other destructive fishing practices,” the report says.

However, experts argue duplication of such a policy would not exactly work as desired here in Kenya.

“What is more likely to happen is that this will cause conflict between fishermen and the enforcers. The most probable recommendation would be to work with the fishermen who are out there in the sea and educate them on the importance of parrotfish. At the end of the day they are going to be protectors of these important fish species,” Thomas Sberna, a marine technical advisor with the IUCN East and South Africa says.

While experts believe the best policy would be one that involves the fishermen, fishermen argue they have been left out of the conversation on parrotfish and other herbivores fish species.

Hamid Omar, Wavuvi association national chair blames the lack of engagement on the communication barrier between researchers and fishermen.

“We are experts in fishing and not experts in Marine research. We continue to fish some of the species you mentioned. If only the researchers can share the findings of their research whenever they write a report, the fishermen would be in a better position to become marine protectors” Omar says.

*Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network*